| History of Jerusalem | |||||||||||||||||

Jerusalem is considered a holy city by three major faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—and figures prominently in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Since 1004 BCE, when King David established Jerusalem as the capital of his kingdom, there has been a continuous Jewish presence in Jerusalem, the holiest city in Judaism. Following the building of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the designation of other holy sites by Constantine the Great in 333 CE, Jerusalem became a destination of Christian pilgrimages. During Umayyad rule from 661 to 750 CE, the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque were built on the site where the Jewish Temples had once stood, and Jerusalem became the third holiest city in Islam.

Jews have constituted the largest ethnic group in Jerusalem since 1820. According to Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, "In the second half of the nineteenth century and at the end of that century, Jews comprised the majority of the population of the Old City ..." (Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century). Martin Gilbert reports that 6,000 Jews resided in Jerusalem in 1838, compared to 5,000 Muslims and 3,000 Christians (Jerusalem: Rebirth of a City). Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1853 "assessed the Jewish population of Jerusalem in 1844 at 7,120, making them the biggest single religious group in the city." (Terence Prittie, Whose Jerusalem?). And others estimated the number of Jewish residents of Jerusalem at the time as even higher. Until about 1860, Jerusalem residents lived almost exclusively within the walls of the Old City, in east Jerusalem. Between 1860 and 1948, Jews lived in both eastern and western Jerusalem.

During the 19 years when Jordan occupied eastern Jerusalem and its holy sites (1948-1967), Jerusalem was divided. Jews were expelled from eastern Jerusalem and barred from visiting their holy places.

As a result of the Six Day War, the entire city of Jerusalem and its holy sites came under Jewish control. Israel reunified the city, extending Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to the parts previously occupied by Jordan. The Israeli Knesset passed laws to protect holy sites and ensure freedom of worship to all, and offered Israeli citizenship to Jerusalem’s Arab residents, most of whom declined.

Since 1967, Jerusalem has become a focal point of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. In 1980, Israel passed the Basic Law: Jerusalem Capital of Israel, reaffirming the unified Jerusalem as its eternal, undivided capital. Palestinians insist Jerusalem must be the capital of their intended state.

Jerusalem in Jewish Tradition

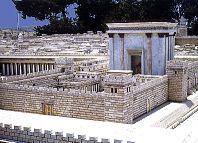

Jerusalem, Judaism’s holiest city, is mentioned hundreds of times in the Hebrew Bible. It was the capital city of ancient Jewish kingdoms and home to Judaism’s holiest Temple (Beit HaMikdash). Jews from all over the ancient world would make pilgrimages to the Beit HaMikdash three times a year to participate in worship and festivities, as commanded in the Torah. Jerusalem and the Beit HaMikdash have remained the focus of Jewish longing, aspiration, and prayers. Daily prayers (said while facing Jerusalem and the Temple Mount) and grace after meals include multiple supplications for the restoration of Jerusalem and the Beit HaMikdash. Jews still maintain the 9th day of the Hebrew month of Av, the date on which both the First and Second Temples were destroyed, as a day of mourning. The Jewish wedding ceremony concludes with the chanting of the biblical phrase, “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its cunning,” and the breaking of a glass by the groom to commemorate the destruction of the Temples. And Yom Kippur services and the Passover Seder conclude each year with the phrase “Next Year in Jerusalem.”

The Temple Mount is the holiest site in Judaism. The Temple was built, according to Jewish tradition, on the Even Hashtiya, the foundation stone upon which the world was created. This is considered the epicenter of Judaism, where the Divine Presence (Shechina) rests, where the biblical Isaac was brought for sacrifice, where the Holy of Holies and Ark of the Covenant housing the Ten Commandments once stood, and where the Temple was again rebuilt in 515 BCE before being destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. The Temple Mount is also known as Mount Moriah (Har HaMoriah), mentioned frequently in the Bible.

The Western Wall (Kotel Hama’aravi, known simply as the Wall or Kotel) is the remnant of the outer retaining wall built by Herod to level the ground and expand the area housing the Second Jewish Temple. Its holiness derives from its proximity to the Temple site and specifically its proximity to the Western Wall of the Temple’s Holy of Holies (Kodesh Hakodashim---the inner sanctuary that housed the Ark of the Covenant–the Aron HaBrit–and where the High Priest–Kohen Gadol--alone was permitted to enter on Yom Kippur). According to Midrashic sources, the Divine Presence never departed from the Western wall of the Temple’s Holy of Holies. For the last several hundred years, Jews have prayed at Herod’s Western Wall because it was the closest accessible place to Judaism’s holiest site.

Jerusalem in Muslim Tradition

Jerusalem assumed significance as an Islamic holy site during the rule of the Umayyads (661-750 CE). Facing challenge to his power from Ibn al-Zubayr, a rebel who controlled Mecca, the Syrian-based Caliph Abd al Malik sought to consolidate his leadership by establishing a place of worship for his followers in Jerusalem in place of Mecca. He built the Dome of the Rock (Masjid Qubbat As Sakhrah) in 688-691 CE on the spot where the Jewish Temples had stood.

Two decades later, in 715 CE, the Umayyads built another mosque on the Temple Mount which they named the Furthest Mosque (Masjid al Aqsa ) to connote the “furthest mosque” alluded to in the Quran (17:1). This was the metaphorical spot from which Mohammed was said to have ascended to heaven in a vision (referred to in Arabic as the Mi’raj) after a night journey from Mecca (the Isra) on a winged steed named Al Buraq.

Although the Quran does not mention Jerusalem or the Temple Mount, the designation of a concrete site to what had been until then just a figurative name provided Muslims with a new religious focus. Several Qur'anic verses were subsequently construed to be obliquely referring to Jerusalem. The Temple Mount was renamed by Muslims the Noble Sanctuary (al Haram al Sharif).

Over the years, Jerusalem’s stature as an Islamic holy city has waxed and waned. During the period between 1948 and 1967 when under Jordanian control, Jerusalem and its holy sites were largely neglected by the Muslim world. Since Israel gained control of East Jerusalem and reunified the city, however, there has been a growing attempt by Palestinians to marshal the religious fervor of the Arab and Muslim world in order to wrest Jerusalem from Israel.

Jerusalem in Christian Tradition

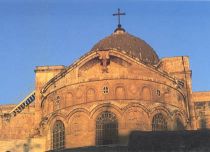

According to Christian tradition, many of the events in Jesus's life and ministry took place in the Holy City. The Last Supper, referring to the final meal shared by Jesus with his disciples before his death, is believed to have taken place in the “Upper Room”or Coenaculum, on the second floor of a building over King David’s tomb on Mount Zion. The Garden of Gethsemane — according to the New Testament, the place where Jesus suffered for the sins of the world the night before he was crucified — is located at the bottom of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. On the Mount of Olives is the Shrine of the Ascension, where Jesus is believed to have ascended to heaven. (It is now run by Muslims and a dome covers the structure.) The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built by Constantine the Great to mark the site of the Resurrection, stands within the walls of the Old City. The remains of Golgotha, the hill upon which Jesus was crucified, is believed to lie inside the church. The church houses priests from the Roman Catholic Church and from numerous Eastern Orthodox traditions. The Via Dolorosa, or “Way of Sorrows,” leading to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, is the traditional path taken by Christians pilgrims to symbolically relive the events of Jesus’ passion. Because of Jesus's historical connection to these and other locations, Jerusalem is venerated by Christians throughout the world.

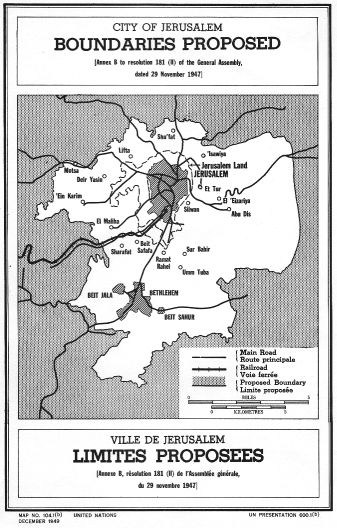

Partition Plan: Corpus Separatum

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly recommended Palestine be partitioned into two states–Arab and Jewish. The plan called for Jerusalem to become a corpus separatum, an international city administered by the UN, for an interval of 10 years, after which the city’s status was to be redetermined in a referendum. While Jewish leaders reluctantly accepted this, Arab leaders rejected the entire plan, including Jerusalem’s internationalization. Arab delegates to the UN declared the partition invalid. Deadly Arab attacks on Jewish residents of Palestine increased, and Arab forces blockaded the road to Jerusalem. When Israel declared Independence in May 1948, five neighboring Arab countries invaded the new state.

1948 Arab-Israeli War

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Transjordan’s Arab Legion attempted to capture the entire city of Jerusalem, shelling it and cutting off its Jewish residents from the coastal plain. Western portions of Jerusalem came under Israel’s control only after Israeli forces broke the Arab siege of the city. In the first four weeks of Arab attacks, 200 Jewish civilians were killed and over 1,000 were wounded in Jerusalem. But, defending themselves, Israeli forces managed to capture some suburbs and villages from the Arabs.

The Israeli defenders were not as successful in protecting the Jewish community of eastern Jerusalem. On May 28, 1948, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City fell to the Arab Legion. After 10 months of fighting, an armistice agreement was signed on April 3, 1949, dividing Jerusalem along the November 1948 ceasefire lines of Israeli and Transjordanian forces, with several areas of no-man’s land. The armistice line served as a temporary border between what had formerly been two mixed communities. Western Jerusalem became Israel’s capital city, while eastern Jerusalem, including the holy sites, was occupied by Transjordan, which in 1949 became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The city was essentially divided between two armed camps separated by barbed wire, concrete walls, minefields and bunkers.

1948-1967: Jordanian Occupation of Eastern JerusalemDestruction and Desecration of Religious Sites

Upon its capture by the Arab Legion, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City was destroyed and its residents expelled. Fifty-eight synagogues—some hundreds of years old—were destroyed, their contents looted and desecrated. Some Jewish religious sites were turned into chicken coops or animal stalls. The Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, where Jews had been burying their dead for over 2500 years, was ransacked; graves were desecrated; thousands of tombstones were smashed and used as building material, paving stones or for latrines in Arab Legion army camps. The Intercontinental Hotel was built on top of the cemetery and graves were demolished to make way for a highway to the hotel. The Western Wall became a slum area.

Jordan’s Illegal Annexation

In 1950, Jordan annexed the territories it had captured in the 1948 war—eastern Jerusalem and the West Bank. The April 24th resolution declared “its support for complete unity between the two sides of the Jordan and their union into one State, which is the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, at whose head reigns King Abdullah Ibn al Husain...”

Great Britain and Pakistan were the only countries that recognized Jordan’s annexation of the West Bank – all other nations, including the Arab states, rejected it. However, Great Britain never recognized Jordan's annexation of eastern Jerusalem. It viewed both Jordan’s 1950 annexation and Israel’s annexation of west Jerusalem as illegal.

Religious Restrictions and Denial of Access to Holy Sites

In direct contravention of the 1949 armistice agreements, Jordan did not permit Jews access to their holy sites or to the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives.

Article VIII of the Israel Jordan Armistice Agreement (April 3, 1949) established a special committee which would “direct its attention to the formulation of agreed plans and arrangements” including “free access to the Holy Places and cultural institutions and use of the cemetery on the Mount of Olives.” Nevertheless, and despite numerous requests by Israeli officials and Jewish groups to the UN, the U.S., and others to attempt to enforce the armistice agreement, Jews were denied access to the Western Wall, the Jewish cemetery and all religious sites in eastern Jerusalem. The armistice lines were sealed as Jordanian snipers would perch on the walls of the Old City and shoot at Israelis across the lines.

Israeli Arabs, too, were denied access to the Al Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock, but their Muslim sites in eastern Jerusalem were respected.

While Christians, unlike Jews, were allowed access to their holy sites, they too were subject to restrictions under Jordanian law. There were limits on the numbers of Christian pilgrims permitted into the Old City and Bethlehem during Christmas and Easter. Christian charities and religious institutions were prohibited from buying real estate in Jerusalem or owning property near holy sites. And Christian schools were subject to strict controls. They were required to teach in Arabic, close on Friday, the Muslim holy day, and teach all students the Koran. At the same time, they were not allowed to teach Christian religious material to non-Christians.

1967: Reunification of Jerusalem

During the 1967 war, Israel appealed to Jordan to stay out of the war, but despite this appeal, Jordanian forces fired artillery barrages from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Although Israeli forces did not respond initially, not wanting to open up a Jordanian front in the war, Jordan continued to attack and occupied UN headquarters in Jerusalem. Israeli forces fought back and within two days managed to repulse the Jordanian forces and retake eastern Jerusalem. (For more details, see Six Day War: Jordanian Front)

On June 7, 1967, IDF paratroopers advanced through the Old City toward the Temple Mount and the Western Wall, bringing Jerusalem’s holiest site under Jewish control for the first time in 2000 years. There are sound recordings of the scene, as the commander of the brigade,Lt. General Mordechai (Motta) Gur, approaches the Old City and announces to his company commanders, “We’re sitting right now on the ridge and we’re seeing the Old City. Shortly we’re going to go in to the Old City of Jerusalem, that all generations have dreamed about. We will be the first to enter the Old City...” and shortly afterwards, “The Temple Mount is in our hands! I repeat, the Temple Mount is in our hands!” General Rabbi Shlomo Goren, chief chaplain of the IDF, sounded the Shofar at the Western Wall to signify its liberation. To Israelis and Jews all over the world, this was a joyous and momentous occasion. Many considered it a gift from God.

In a statement at the Western Wall, Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan indicated Israel’s peaceful intent and pledged to preserve religious freedom for all faiths in Jerusalem:

Before visiting the Western Wall, Prime Minister Levi Eshkol met with the spiritual leaders of different faiths in his office and issued a declaration of peace, assuring that all holy sites would be protected and that all faiths would be free to worship at their holy sites in Jerusalem. He declared his intention to give the spiritual leaders of the various religions internal management of their own Holy Sites. Defense Minister Dayan immediately ceded internal administrative control of the Temple Mount compound to the Jordanian Waqf (Islamic trust) while overall security control of the area was maintained by Israel. Dayan announced that Jews would be allowed to visit the Temple Mount, but not to hold religious services there.

Dayan also gave immediate orders to demolish the anti-sniping walls, clear the minefields and removed the barbed-wire barriers which marked the partition of Jerusalem. Within weeks, free movement through Jerusalem became possible and hundreds of thousands of Israeli Jews flocked to the Old City to glimpse the Western Wall and touch its stones. Israeli Muslims were permitted to pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock for the first time since 1948. And Israeli Christians came to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

On June 27, 1967, the Israeli Knesset extended Israel’s legal and administrative jurisdiction to all of Jerusalem, and expanded the city’s municipal borders. Eshkol again assured the spiritual leaders of all faiths that Israel was determined to protect the Holy Places. The Knesset passed the Protection of Holy Places Law granting special legal status to the Holy Sites and making it a criminal offence to desecrate or violate them, or to impede freedom of access to them. Jerusalem became a reunified city that ensured freedom of religion and access to holy sites for all.

The religious freedoms enjoyed by Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the reunified Jerusalem had been unheard of during Jordanian occupation of the city, prompting even a former Jordanian ambassador to the United Nations, Adnan Abu Odeh, to acknowledge that "the situation in Jerusalem prior to 1967 [under Jordanian rule] was one of ... religious exclusion" whereas post-1967, Israel seeks "to reach a point of religious inclusion ..." (The Catholic University of America Law Review, Spring 1996).

1980: Basic Law: Jerusalem Capital of Israel

Since 1958, 14 basic laws were passed by the Israeli Knesset. These laws, pertaining to the government, president, army, economy, judiciary, land, human rights, and more are intended to form the essence of the constitution of the State of Israel. In 1980, the Israeli Knesset passed a basic law declaring reunified Jerusalem the eternal capital of Israel. The law provides for protection of and freedom of access to each religion's holy sites. Below is the text of the law, which can be accessed on the Israeli Knesset Web site.

| |||||||||||||||||

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

History of Jerusalem

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

How can I help fight Delegitimization?

ReplyDeleteIAN’s (Israel Action Network) Community Mobilization Manual, outlines 10 steps for combating Delegitimization in your communities:

• TIP 1: Understand the Challenge

• TIP 2: Is this Criticism or Delegitimization?

• TIP 3: Know your Facts; Do the Research

• TIP 4: Identify your Audience: Supporters; Opponents; Target Communities of Concerned Individuals and Organizations

• TIP 5: Take an Inventory of your Assets: People; Skills; Program; Missions; Cultural Events; Monetary Resources

• TIP 6: Map Out your Strategies

• TIP 7: Clean your Message Slate

• TIP 8: Engage

• TIP 9: Stay Connected and Networked

• TIP 10: Evaluate; Applaud Successes; Reward Advocates; Invest in What Works

How can I help fight Delegitimization?

ReplyDeleteIAN’s (Israel Action Network) Community Mobilization Manual, outlines 10 steps for combating Delegitimization in your communities:

• TIP 1: Understand the Challenge

• TIP 2: Is this Criticism or Delegitimization?

• TIP 3: Know your Facts; Do the Research

• TIP 4: Identify your Audience: Supporters; Opponents; Target Communities of Concerned Individuals and Organizations

• TIP 5: Take an Inventory of your Assets: People; Skills; Program; Missions; Cultural Events; Monetary Resources

• TIP 6: Map Out your Strategies

• TIP 7: Clean your Message Slate

• TIP 8: Engage

• TIP 9: Stay Connected and Networked

• TIP 10: Evaluate; Applaud Successes; Reward Advocates; Invest in What Works

ReplyDeleteGeorge Adam Smith, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land

David Lloyd George was the British Prime Minister from December 7, 1916-October 22.

It was during Lloyd George's time in office that the British conquered Palestine, the Balfour Declaration was adopted, and the Peace conferences that concluded with the Mandate for Palestine being accepted by the British all took place.

Lloyd George had often cited the works of a Scottish Biblical scholar named George Adam Smith as the authority on the ancient Holy Land. It was Smith's maps that were to be used in determining the borders of Jewish Palestine. The two maps below are maps that detail Jewish rule during the times of the Jewish Monarchs and the Second Temple Period.

For more information about George Adam Smith and his maps being used to determine the borders of the Jewish National Home, see the article below the maps.

Smith's maps are available as a PDF online