Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries - Due to persecution and violence

Plitim:

The '''Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries''' or '''Jewish exodus from Arab countries''' ( '''') was the departure, flight, evacuation and migration, of 850,000 Jews, primarily of Sephardi+ and Mizrahi+background, from Arab+ and Muslim countries+, mainly from 1948 onwards.

A small-scale Jewish exodus had begun in many countries in the early decades of the 20th century, although the only substantial aliyah+ came from Yemen and Syria. Prior to the creation of Israel+ in 1948, approximately 800,000 Jews were living in lands that now make up the Arab world+. Of these, just under two-thirds lived in the French and Italian-controlled North Africa+, 15–20% in the Kingdom of Iraq+, approximately 10% in the Kingdom of Egypt+ and approximately 7% in the Kingdom of Yemen+. A further 200,000 lived in Pahlavi Iran+ and the Republic of Turkey+. In 2009, only 26,000 Jews lived in Arab countries and 26,000 in Turkey+.

In 1944, the Zionist leadership in Mandate Palestine approved the One Million Plan+, for the large scale immigration of Jews within 18 months, targeting various Jewish communities, including those in Islamic countries. Later, after the establishment of the State of Israel, a new plan for 600,000 immigrants over 4 years was made.

The first large-scale exoduses took place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, primarily in Iraq, Yemen and Libya. In these cases over 90% of the Jewish population left, despite the necessity of leaving their property behind.

Two hundred sixty thousand Jews from Arab countries immigrated to Israel+ between 1948 and 1951, amounting for 56% of the total immigration to the newly founded state.

Later waves peaked at different times in different regions over the subsequent decades. The peak of the exodus from Egypt occurred in 1956 following the Suez Crisis+. The exodus in the North African Arab countries peaked in the 1960s. Lebanon was the only Arab country to see a temporary increase in its Jewish population during this period, due to a temporal influx of Jews from other Arab countries, although by the mid-1970s the Jewish community of Lebanon had also dwindled. Six hundred thousand Jews from Arab and Muslim countries had reached Israel by 1972.Malka Hillel Shulewitz, ''The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands'', Continuum 2001, pp. 139 and 155.Ada Aharoni , Historical Society of Jews from Egypt website. Accessed 1 February 2009. The descendants of the Jewish immigrants from the region, today known as Mizrahi Jews+ ("Eastern Jews"), currently constitute more than half of the total population of Israel, partially as a result of their higher fertility rate+.

The reasons for the exodus included push factors+, such as persecution+, antisemitism+, political instability, poverty and minor expulsions; together with pull factors+, such as the desire to fulfill Zionist+ yearnings or find a better economic status and a secure home in Europe or the Americas.

The history of the exodus is politicized, given its proposed relevance to the historical narrative of the Arab-Israeli conflict+. When presenting the history, those who view the Jewish exodus as analogous to the 1948 Palestinian exodus+ generally emphasize the push factors and consider those who left as refugees, while those who do not, emphasize the pull factors and consider them willing immigrants.

By the time of the Muslim conquests+ of the 7th century, ancient Jewish communities had existed in many parts of the Middle East and North Africa since Antiquity. Jews under Islamic rule+ were given the status of dhimmi+, along with certain other pre-Islamic religious groups. As such, these groups were accorded certain rights as "People of the Book+".

During waves of persecution in Medieval Europe+, many Jews found refuge in Muslim lands. For instance, Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula+ were invited to settle+ in various parts of the Ottoman Empire+, where they would often form a prosperous model minority+ of merchants acting as intermediaries+ for their Muslim rulers.

The immigration restrictions of the British White Paper of 1939+ meant that such a plan was not able to be put into effect. After Israel was established, Ben Gurion's government presented the Knesset with a new plan - to double the population of 600,000 within 4 years. This immigration policy+ had some opposition within the new Israeli government, however, the force of Ben-Gurion's influence and insistence ensured that unrestricted immigration continued.sfn|Hakohen|2003|p=247|ps=: "On several occasions, resolutions were passed to limit immigration from European and Arab countries alike.

However, these limits were never put into practice, mainly due to the opposition of Ben-Gurion. As a driving force in the emergency of the state, Ben-Gurion—both prime minister and minister of defense—carried enormous weight with his veto. His insistence on the right of every Jew to immigrate proved victorious. He would not allow himself to be swayed by financial or other considerations. It was he who orchestrated the large-scale action that enabled the Jews to leave Eastern Europe and Islamic countries, and it was he who effectively forged Israel's foreign policy. Through a series of clandestine activities carried out overseas by the Foreign Office, the Jewish Agency, the Mossad le-Aliyah, and the Joint Distribution Committee, the road was paved for mass immigration."

The first organizational measure of the Plan was the late 1943 general plan of action entitled 'The Uniform Pioneer to the Eastern Lands’, which would offer a course for emissaries from the Jewish Agency Immigration Department to later be sent Islamic countries.: Section "THE ONE MILLION PLAN AND THE OPERATIVE POLICY OF ZIONISM": "Making mass immigration from Islamic countries a political objective required preparations to ensure that the immigrants would actually come. In the course of Zionist activity during World War II, the Yishuv leaders had discovered that the Jews in these countries were not clamouring to emigrate, that there was no comprehensive Zionist activity there and that the Zionist cadre active there was extremely limited in scope and in its ability to have an impact... The first organizational measure was the Jewish Agency’s decision to offer a course for emissaries who would then be posted to Islamic countries. In the second half of 1943, a general plan of action was drawn up. Entitled 'The Uniform Pioneer to the Eastern Lands’, the plan proclaimed the concept of an ingathering of exiles and the revival of the Jewish people in Palestine as its central theme... To ensure implementation of the plan, it was decided that the emissaries would be sent out by the Jewish Agency Immigration Department and that it, not the Histadrut—as had been the case until then—would be responsible for the enterprise... The Uniform Pioneer Plan set a precedent for the Zionist movement’s patronizing attitude toward its adherents in the Islamic countries and later in Israel. These activities in Islamic countries lost their urgency and attraction after WWII, and the boost in resources they received dwindled. The number of activists in these countries was minuscule compared to Europe, and there were not even enough of them to maintain what was already established.

One of the issues that came up during discussions of the One Million Plan, particularly after the Baghdad pogrom+ and reports of antisemitic manifestations in Arab countries, was the security of Jewish communities in Islamic countries. In a 1943 Mapai central comittee speech, Eliyahu Dobkin+, the head of the Jewish Agency's immigration department, said: "The very same day that brings redemption and salvation to European Jewry will be the most dangerous day of all for the exiles in Arab lands... these Jews will face great danger, danger of terrible slaughter... Our first task is therefor to save these Jews." and Ben-Gurion wrote at a similar time of "the catastrophe that the Jews in eastern lands are expected to face as a result of Zionism", although these gloomy forecasts proved false.

In the 19th century, Francization+ of Jews in the French colonial Maghreb+, due to the work of organizations such as the Alliance Israelite Universelle+ and French policies such as the Algerian citizenship decree of 1870+, resulted in a separation of the community from the local Muslims.

The French began the conquest of Algeria in 1830+. The following century had a profound influence on the status of the Algerian Jews; following the 1870 "Decrée Crémieux", they were elevated from the protected minority dhimmi status to French citizens of the colonial power. The decree began a wave of Pied-Noir+-led anti-Jewish protests, which the Muslim community did not participate in, to the disappointment of the European agitators. Anti-Jewish riots took place at 1897 in Oran+ and in Constantine+ in 1934 when 34 Jews were killed.

Neighbouring Husainid Tunisia+ began to come under European influence in the late 1860s and became a French protectorate+ in 1881. Since the 1837 accession of Ahmed Bey+, and continued by his successor Muhammed Bey+, Tunisia's Jews were elevated within Tunisia society with improved freedom and security, which was confirmed and safeguarded during the French protectorate. Around a third of Tunisian Jews took French citizenship during the protectorate.

Morocco, which had remained independent during the 19th century, became a French protectorate+ in 1912. However, during less than half a century of colonization, the equilibrium between Jews and Muslims in Morocco was upset, and the Jewish community was again positioned between the colonisers and the Muslim majority. French penetration into Morocco between 1906 and 1912 created significant Morocco Muslim resentment, resulting in nationwide protests and military unrest. During the period a number of anti-European or anti-French protests extended to include anti-Jewish manifestations, such as in Casablanca+, Oujda+ and Fes+ in 1907-08 and later in the 1912 Fes riots+.

The situation in colonial Libya was similar; as for the French in the other Maghreb countries, the Italian influence in Libya+ was welcomed by the Jewish community, increasing their separation from the non-Jewish Libyans.

The Alliance Israelite Universelle, founded in France in 1860, set up schools in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia as early as 1863.

During World War II, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya came under Nazi+ or Vichy French+ occupation and their Jews were subject to various persecution. In Libya, the Axis powers established labor camps+ to which many Jews were forcibly deported.". Retrieved July 1, 2006 In other areas Nazi propaganda+ targeted Arab populations to in National Socialist propaganda contributed to the transfer of racial antisemitism+ to the Arab world and is likely to have unsettled Jewish communities. An anti-Jewish riot took place in Casablanca in 1942 in the wake of Operation Torch, where a local mob attacked the Jewish mellah+. However, according to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem+'s Dr. Haim Saadon, "Relatively good ties between Jews and Muslims in North Africa during World War II stand in stark contrast to the treatment of their co-religionists by gentiles in Europe.", 24 January 2011, ''The Jerusalem Post+''

As in Tunisia and Algeria, Moroccan Jews+ did not face expulsion or asset confiscation or any similar government persecution during the period of exile, and Zionist agents were allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.

In Morocco the Vichy regime during World War II passed discriminatory laws against Jews; for example, Jews were no longer able to get any form of credit, Jews who had homes or businesses in European neighborhoods were expelled, and quotas were imposed limiting the percentage of Jews allowed to practice professions such as law and medicine to no more than two percent. King Mohammed V+ expressed his personal distaste for these laws, assuring Moroccan Jewish leaders that he would never lay a hand "upon either their persons or property". While there is no concrete evidence of him actually taking any actions to defend Morocco's Jews, it has been argued that he may have worked on their behalf behind the scenes.

In June 1948, soon after Israel was established+ and in the midst of the first Arab-Israeli war+, violent anti-Jewish riots+ broke out in Oujda and Djerada+, leading to deaths of 44 Jews. In 1948–9, after the massacres, 18,000 Moroccan Jews left the country for Israel. Later, however, the Jewish exodus from Morocco slowed to a few thousand a year. Through the early 1950s, Zionist+ organizations encouraged emigration, particularly in the poorer south of the country, seeing Moroccan Jews as valuable contributors to the Jewish State:

Incidents of anti-Jewish violence continued through the 1950s, although French officials later stated that Moroccan Jews "had suffered comparatively fewer troubles than the wider European population" during the struggle for independence. , JTA, 24 August 1953. In the same month French security forces prevented a mob from breaking into the Jewish Mellah of Rabat+. In 1954, a nationalist event in the town of Petitjean (known today as Sidi Kacem+) turned into an anti-Jewish riot and resulted in the death of 6 Jewish merchants fromMarrakesh+. However, according to Francis Lacoste, French Resident-General in Morocco+, "the ethnicity of the Petitjean victims was coincidental, terrorism rarely targeted Jews, and fears about their future were unwarranted."sfn|Mandel|2014|p=37|ps=: "In August 1954, just after the first anniversary of Frances exile of Morocco's Sultan Muhammad V to Madagascar for his nationalist sympathies, seven Jews were killed in the town of Petitjean. Part of the wider violence associated with challenging French rule in the region, the murders reflected the escalating nature of the conflict.... In the opinion of Francis Lacoste, Morocco's resident general, the ethnicity of the Petitjean victims was coincidental, terrorism rarely targeted Jews, and fears about their future were unwarranted." In 1955, a mob broke into the Jewish Mellah in Mazagan (known today as El Jadida+) and caused its 1700 Jewish residents to flee to the European quarters of the city. The houses of some 200 Jews were too badly damaged during the riots for them to return.

In 1956, Morocco attained independence. Jews occupied several political positions, including three parliamentary seats and the cabinet position of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. However, that minister, Leon Benzaquen+, did not survive the first cabinet reshuffling, and no Jew was appointed again to a cabinet position. Although the relations with the Jewish community at the highest levels of government were cordial, these attitudes were not shared by the lower ranks of officialdom, which exhibited attitudes that ranged from traditional contempt to outright hostility.Stillman, 2003, p. 173. Morocco's increasing identification with the Arab world+, and pressure on Jewish educational institutions to arabize+ and conform culturally added to the fears of Moroccan Jews. As a result, emigration to Israel jumped from 8,171 persons in 1954 to 24,994 in 1955, increasing further in 1956.

Between 1956 and 1961, emigration to Israel was prohibited by law; clandestine emigration continued, and a further 18,000 Jews left Morocco. On 10 January 1961 the ''Egoz+'', a ship carrying Jews attempting to flee the country, sank off the northern coast of Morocco; the negative publicity associated with this event prompted King Mohammed V to allow Jewish emigration, and over the three following years, more than 70,000 Moroccan Jews left the country. By 1967, only 50,000 Jews remained.Stillman, 2003, p. 175.

The 1967 Six-Day War+ led to increased Arab-Jewish tensions worldwide, including in Morocco, and significant Jewish emigration out of the country continued. By the early 1970s, the Jewish population of Morocco fell to 25,000; however, most of the emigrants went to France, Belgium, Spain, and Canada, rather than Israel.

Despite their dwindling numbers, Jews continue to play a notable role in Morocco; the King retains a Jewish senior adviser, André Azoulay+, and Jewish schools and synagogues receive government subsidies. Despite this, Jewish targets have sometimes been attacked (notably the 2003 bombing attacks+ on a Jewish community center in Casablanca), and there is sporadic anti-Semitic rhetoric from radical Islamist groups. Invitations from the late King Hassan II+ for Jews to return to Morocco have not been taken up by the people who had emigrated.

According to Esther Benbassa, the migration of Jews from the Maghreb countries was prompted by uncertainty about the future. In 1948, over 250,000–265,000 Jews lived in Morocco. By 2001 an estimated 5,230 remained.

As in Tunisia and Morocco, Algerian Jews did not face expulsion or asset confiscation or any similar government persecution under French colonial administration, and Zionist agents were allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.

Jewish emigration from Algeria was part of a wider ending of French colonial control and the related social, economic and cultural changes. Emigration peaked during the Algerian War+ of 1954–1962, during which thousands of Muslims, Christians and Jews left the country,

As the Algerian Revolution+ began to intensify in the late 1950s and early 1960s, most of Algeria's 140,000 Jews began to leave. The community had lived mainly in Algiers+ and Blida+, Constantine, and Oran.

Almost all Jews of Algeria left upon independence in 1962, particularly as "the Algerian Nationality Code of 1963 excluded non-Muslims from acquiring citizenship", allowing citizenship only to those Algerians who had Muslim fathers and paternal grandfathers. Algeria's 140,000 Jews, who had French citizenship since 1870 (briefly revoked by Vichy France in 1940) left mostly for France, although some went to Israel.

The Algiers synagogue was consequently abandoned after 1994.

Jewish migration from North Africa to France led to the rejuvenation of the French Jewish+ community, which is now the third largest in the world.

As in Morocco and Algeria, Tunisian Jews did not face expulsion or asset confiscation or any similar government persecution during the period of exile, and Zionist agents were allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.

In 1948, approximately 105,000 Jews lived in Tunisia. About 1,500 remain today, mostly in Djerba+, Tunis+, and Zarzis+. Following Tunisia's independence from France in 1956, a number of anti-Jewish policies led to emigration, of which half went to Israel and the other half to France. After attacks in 1967, Jewish emigration both to Israel and France accelerated. There were also attacks in 1982, 1985, and most recently in 2002 when a bombing in Djerba+ took 21 lives (most of them German tourists) near the local synagogue, a terrorist attack claimed by Al-Qaeda+.

According to Maurice Roumani, a Libyan emigrant who was previously the Executive Director of WOJAC+, the most important factors that influenced the Libyan Jewish community to emigrate were "the scars left from the last years of the Italian occupation and the entry of the British Military in 1943 accompanied by the Jewish Palestinian soldiers".

In 1942, German troops+ fighting the Allies in North Africa+ occupied the Jewish quarter of Benghazi+, plundering shops and deporting more than 2,000 Jews across the desert. Sent to work in labor camps, more than one-fifth of that group of Jews perished. At the time, most of the Jews were living in cities of Tripoli+ and Benghazi and there were smaller numbers in Bayda+ and Misrata+. Following the allied victory at the Battle of El Agheila+ in December 1942, German and Italian troops were driven out of Libya. The British installed the Palestine Regiment+ in Cyrenaica+, which later became the core of the Jewish Brigade+, which was later also stationed in Tripolitania+. The pro-Zionist soldiers encouraged the spread of Zionism throughout the local Jewish population

In 1943, Mossad LeAliyah Bet+ began to send emissaries to prepare the infrastructure for the emigration of the Libyan Jewish community.

Following the liberation of North Africa by allied forces, antisemitic in Gil Shefler+ writes that "As awful as the pogrom in Libya was, it was still a relatively isolated occurrence compared to the mass murders of Jews by locals in Eastern Europe." The same year, violent anti-Jewish violence also occurred in Cairo+, which resulted in 10 Jewish victims.

In 1948, about 38,000 Jews lived in Libya. The pogroms continued in June 1948, when 15 Jews were killed and 280 Jewish homes destroyed. In November 1948, a few months after the events in Tripoli, the American consul in Tripoli, Orray Taft Jr., reported that: "There is reason to believe that the Jewish Community has become more aggressive as the result of the Jewish victories in Palestine. There is also reason to believe that the community here is receiving instructions and guidance from the State of Israel. Whether or not the change in attitude is the result of instructions or a progressive aggressiveness is hard to determine. Even with the aggressiveness or perhaps because of it, both Jewish and Arab leaders inform me that the inter-racial relations are better now than they have been for several years and that understanding, tolerance and cooperation are present at any top level meeting between the leaders of the two communities."

Immigration to Israel began in 1949, following the establishment of a Jewish Agency for Israel+ office in Tripoli. According to Harvey E. Goldberg, "a number of Libyan Jews" believe that the Jewish Agency was behind the riots, given that the riots helped them achieve their goal. Between the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and Libyan independence in December 1951 over 30,000 Libyan Jews emigrated to Israel.

In 1967, during the Six-Day War+, the Jewish population of 4,000 was again subjected to riots in which 18 were killed, and many more injured. According to David Harris+, the Executive Director of the Jewish advocacy organization AJC+, the pro-Western Libyan government of King Idris I+ "faced with a complete breakdown of law and order ... urged the Jews to leave the country temporarily", permitting them each to take one suitcase and the equivalent of $50. In June and July over 4,000 traveled to Italy, where they were assisted by the Jewish Agency for Israel. 1,300 went on to Israel, 2,200 remained in Italy, and most of the rest went to the United States. A few scores remained in Libya and others managed to return between 1967 and 1969.

In 1970 the Libyan government issued new laws that confiscated all the assets of Libya's Jews, issuing in their stead 15-year bonds. However, when the bonds matured no compensation was paid. Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi+ justified this on the grounds that "the alignment of the Jews with Israel, the Arab nations' enemy, has forfeited their right to compensation."

Although the main synagogue in Tripoli was renovated in 1999, it has not reopened for services. The last Jew in Libya, Esmeralda Meghnagi, died in February 2002. Israel is home to about 40,000 Jews of Libyan descent, who maintain unique traditions.

The British mandate over Iraq+ came to an end in June 1930, and in October 1932 the country became independent. The Iraqi government response to the demand of Assyria+n autonomy (a Semitic tribe, affiliated to Nestorian+ church), turned into a bloody massacre+ of Assyrian villagers+ by the Iraqi army in August 1933. This event was the first sign to the Jewish community that minority rights were meaningless under Iraqi monarchy. King Faisal+, known for his liberal policies, died in September 1933, and was succeeded by Ghazi+, his nationalistic anti-British son. Ghazi began promoting Arab nationalist+ organizations, headed by Syrian and Palestinian exiles. With 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine+, they were joined by rebels, such as the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem+. The exiles preached pan-Arab ideology and fostered anti-Zionist propaganda.

Under Iraqi nationalists, the Nazi propaganda began to infiltrate the country, as Nazi Germany was anxious to expand its influence in the Arab world. Dr. Fritz Grobba+, who resided in Iraq since 1932, began to vigorously and systematically disseminate hateful propaganda against Jews. Among other things, Arabic translation of ''Mein Kampf+'' was published and Radio Berlin had begun broadcasting in Arabic language. Anti-Jewish policies had been implemented since 1934, and the confidence of Jews was further shaken by the growing crisis in Palestine in 1936. Between 1936 and 1939 ten Jews were murdered and on eight occasions bombs were thrown on Jewish locations. In 1951, the Iraqi Government made advocating Zionism or belonging to a Zionist organization a crime and ordered the expulsion of Jews who refused to sign a statement of anti-Zionism. Alternative views are of illegal and subsequent legislated emigration, but regarding expulsion, they include "trying to", "wanted to", and "planned to", but no cases of actual expulsions from Iraq. Instead, the bulk of the Jews leaving Iraq did so via Israeli airlifts named Operation Ezra and Nehemiah+ with special permission from the Iraqi government.

In 1941, immediately following the British victory in the Anglo-Iraqi War+, riots known as the Farhud+ broke out in Baghdad+ in the power vacuum+ following the collapse of the pro-Axis+ government of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani+ while the city was in a state of instability. 180 Jews were killed and another 240 wounded; 586 Jewish-owned businesses were looted and 99 Jewish houses were destroyed.

In some accounts the Farhud marked the turning point for Iraq's Jews. Other historians, however, see the pivotal moment for the Iraqi Jewish community much later, between 1948–51, since Jewish communities prospered along with the rest of the country throughout most of the 1940s,Moshe Gat, , quote(1): "[as a result] of the economic boom and the security granted by the government.... Jews who left Iraq immediately after the riots, later returned." Quote(2): "Their dream of integration into Iraqi society had been dealt a severe blow by the farhud but as the years passed self-confidence was restored, since the state continued to protect the Jewish community and they continued to prosper." Quote(3): Quoting Enzo Sereni+: "The Jews have adapted to the new situation with the British occupation, which has again given them the possibility of free movement after months of detention and fear.", "Yet Sasson Somekh insists that the farhud was not 'the beginning of the end'. Indeed, he claims it was soon 'almost erased from the collective Jewish memory', washed away by 'the prosperity experienced by the entire city from 1941 to 1948'. Somekh, who was born in 1933, remembers the 1940s as a 'golden age' of 'security', 'recovery' and ‘consolidation', in which the 'Jewish community had regained its full creative drive'. Jews built new homes, schools and hospitals, showing every sign of wanting to stay. They took part in politics as never before; at Bretton Woods, Iraq was represented by Ibrahim al-Kabir, the Jewish finance minister. Some joined the Zionist underground, but many more waved the red flag. Liberal nationalists and Communists rallied people behind a conception of national identity far more inclusive than the Golden Square's Pan-Arabism, allowing Jews to join ranks with other Iraqis – even in opposition to the British and Nuri al-Said, who did not take their ingratitude lightly." and many Jews who left Iraq following the Farhud returned to the country shortly thereafter and permanent emigration did not accelerate significantly until 1950–51.

Either way, the Farhud is broadly understood to mark the start of a process of politicization of the Iraqi Jews in the 1940s, primarily among the younger population, especially as a result of the impact it had on hopes of long term integration into Iraqi society. In the direct aftermath of the Farhud, many joined the Iraqi Communist Party+ in order to protect the Jews of Baghdad, yet they did not want to leave the country and rather sought to fight for better conditions in Iraq itself. At the same time the Iraqi government that had taken over after the Farhud reassured the Iraqi Jewish community, and normal life soon returned to Baghdad, which saw a marked betterment of its economic situation during World War II.

Shortly after the Farhud in 1941, Mossad LeAliyah Bet sent emissaries to Iraq to begin to organize emigration to Israel, initially by recruiting people to teach Hebrew and hold lectures on Zionism. In late 1942, one of the emissaries explained the size of their task of converting the Iraqi community to Zionism, writing that "we have to admit that there is not much point in [organizing and encouraging emigration].... We are today eating the fruit of many years of neglect, and what we didn't do can't be corrected now through propaganda and creating one-day-old enthusiasm."

In 1948, there were approximately 150,000 Jews in Iraq. The community was concentrated in Baghdad and Basra+. By 2003, there were only about 100 left of this previously thriving community. Around 8,000 Jews left Iraq between 1919–48, with another 2,000 leaving between mid-1948 to mid-1950.Mike Marqusee+, "Diasporic Dimensions" in If I am Not for Myself, Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew, 2011 However, in the wake of the 1950 Denaturalisation+ Act and the 1950–51 Baghdad bombings+, more than 120,000 Jews left the country in less than a year. The Iraqi government convicted and hanged a number of suspected Zionist agents for perpetrating the bombings, but the issue of who was responsible remains a subject of scholarly dispute. In 1969, about 50 of the Jews who remained were executed; 11 were publicly executed after show trial+s and hundred thousand Iraqis marched past the bodies in a carnival-like atmosphere.

Before United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine+ vote, the Iraq's prime minister Nuri al-Said+ told British diplomats that if the United Nations solution was not "satisfactory", "severe measures should [would?] be taken against all Jews in Arab countries". In a speech at the General Assembly Hall at Flushing Meadow, New York, on Friday, 28 November 1947, Iraq's Foreign Minister, Fadel Jamall, included the following statement: "Partition imposed against the will of the majority of the people will jeopardize peace and harmony in the Middle East. Not only the uprising of the Arabs of Palestine is to be expected, but the masses in the Arab world cannot be restrained. The Arab-Jewish relationship in the Arab world will greatly deteriorate. There are more Jews in the Arab world outside of Palestine than there are in Palestine. In Iraq alone, we have about one hundred and fifty thousand Jews who share with Moslems and Christians all the advantages of political and economic rights. Harmony prevails among Moslems, Christians and Jews. But any injustice imposed upon the Arabs of Palestine will disturb the harmony among Jews and non-Jews in Iraq; it will breed inter-religious prejudice and hatred." In 19 February 1949, al-Said acknowledged the bad treatment that the Jews had been victims of in Iraq during the recent months. He warned that unless Israel would behave itself, events might take place concerning the Iraqi Jews. Al-Said's threats had no impact at the political level on the fate of the Jews but were widely published in the media.

In 1948, the country was placed under martial law, and the penalties for Zionism were increased. Courts martial were used to intimidate wealthy Jews, Jews were again dismissed from civil service, quotas were placed on university positions, Jewish businesses were boycotted (E. Black, p. 347) and Shafiq Ades+ (one of the most important anti-Zionist Jewish businessmen in the country) was arrested and publicly hanged for allegedly selling goods to Israel, shocking the community (Tripp, 123). The Jewish community general sentiment was that if a man as well connected and powerful as Shafiq Ades+ could he eliminated by the state, other Jews would not be protected any longer.: "the general sentiment was chat if a man as well connected and powerful as Adas could he eliminated by the state, other Jews would not be protected any longer."

Additionally, like most Arab League+ states, Iraq forbade any legal emigration of its Jews on the grounds that they might go to Israel and could strengthen that state. At the same time, increasing government oppression of the Jews fueled by anti-Israeli sentiment together with public expressions of antisemitism created an atmosphere of fear and uncertaint

Like most Arab League+ states, Iraq initially forbade the emigration of its Jews after the 1948 war on the grounds that allowing them to go to Israel would strengthen that state. However, by 1949 Jews were escaping Iraq at about a rate of 1,000 a month.Simon, Reguer, and Laskier, p. 365 At the time, the British believed that the Zionist underground was agitating in Iraq in order to assist US fund-raising and to "offset the bad impression caused by the Jewish attitudes to Arab refugees".sfn|Shiblak|1986|ps=: "In a confidential telegram sent on 2 November 1949, the British ambassador to Washington explained ... the general view of officials in the State Department is that the [Zionist] agitation has been deliberately worked up for two reasons:

(a) To assist fund-raising in the United States

(b) To create favourable sentiments in the United Nations Assembly to offset the bad impression caused by the Jewish attitudes to Arab refugees. They suggest that the Israeli Government is fully aware of the Iraqi Jews, but is prepared to be callous towards the community, the bulk of which, as Dr Elath+ admitted, has no wish to transfer its allegiance to Israel."

The Iraqi government took in only 5,000 of the c.700,000 Palestinians who became refugees+ in 1948–49 and refused to submit to American and British pressure to admit more. In January 1949, the pro-British Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said discussed the idea of deporting Iraqi Jews to Israel with British officials, who explained that such a proposal would benefit Israel and adversely affect Arab countries. According to Meir-Glitzenstein, such suggestions were "not intended to solve either the problem of the Palestinian Arab refugees or the problem of the Jewish minority in Iraq, but to torpedo plans to resettle Palestinian Arab refugees in Iraq". In July 1949 the British government proposed to Nuri al-Said a population exchange+ in which Iraq would agree to settle 100,000 Palestinian refugees+ in Iraq; Nuri stated that if a fair arrangement could be agreed, "the Iraqi government would permit a voluntary move by Iraqi Jews to Palestine." The Iraqi-British proposal was reported in the press in October 1949. On 14 October 1949 Nuri Al Said raised the exchange of population concept with the economic mission survey. At the Jewish Studies Conference in Melbourne in 2002, Philip Mendes summarised the effect of al-Saids vacillations on Jewish expulsion as: "In addition, the Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri as-Said tentatively canvassed and then shelved the possibility of expelling the Iraqi Jews, and exchanging them for an equal number of Palestinian Arabs."

In March 1950 Iraq reversed their earlier ban on Jewish emigration to Israel and passed a law of one-year duration allowing Jews to emigrate on the condition of relinquishing their Iraqi citizenship. According to Abbas Shiblak+, many scholars state that this was a result of British, American and Israeli political pressure on Tawfiq al-Suwaidi's+ government, with some studies suggesting there were secret negotiations. According to Ian Black+, the Iraqi government was motivated by "economic considerations, chief of which was that almost all the property of departing Jews reverted to the state treasury" and also that "Jews were seen as a restive and potentially troublesome minority that the country was best rid of." Israel mounted an operation called "Operation Ezra and Nehemiah+" to bring as many of the Iraqi Jews as possible to Israel.

The Zionist movement at first tried to regulate the amount of registrants until issues relating to their legal status were clarified. Later, it allowed everyone to register. Two weeks after the law went into force, the Iraqi interior minister demanded a CID investigation over why Jews were not registering. A few hours after the movement allowed registration, four Jews were injured in a bomb attack at a café in Baghdad.

Immediately following the March 1950 Denaturalisation Act, the emigration movement faced significant challenges. Initially, local Zionist activists forbade the Iraqi Jews from registering for emigration with the Iraqi authorities, because the Israeli government was still discussing absorption planning. However, on 8 April, a bomb exploded in a Jewish cafe in Baghdad, and a meeting of the Zionist leadership later that day agreed to allow registration without waiting for the Israeli government; a proclamation encouraging registration was made throughout Iraq in the name of the State of Israel. However, at the same time immigrants were also entering Israel from Poland and Romania, countries in which Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion+assessed there was a risk that the communist authorities would soon "close their gates", and Israel therefore delayed the transportation of Iraqi Jews. As a result, by September 1950, while 70,000 Jews had registered to leave, many selling their property and losing their jobs, only 10,000 had left the country. According to Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, "The thousands of poor Jews who had left or been expelled from the peripheral cities, and who had gone to Baghdad to wait for their opportunity to emigrate, were in an especially bad state. They were housed in public buildings and were being supported by the Jewish community. The situation was intolerable." The delay became a significant problem for the Iraqi government of Nuri al-Said (who replaced Tawfiq al-Suwaidi in mid-September 1950), as the large number of Jews "in limbo" created problems politically, economically and for domestic security. "Particularly infuriating" to the Iraqi government was the fact that the source of the problem was the Israeli government.

As a result of these developments, al-Said was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible. On 21 August 1950 al-Said threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews, and in September 1950, he summoned a representative of the Jewish community and warned the Jewish community of Baghdad to make haste; otherwise, he would take the Jews to the borders himself. On 12 October 1950, Nuri al-Said summoned a senior official of the transport company and made similar threats, justifying the expulsion of Jews by the number of Palestinian Arabs fleeing from Israel.

Two months before the law expired, after about 85,000 Jews had registered, a bombing campaign+ began against the Jewish community of Baghdad. All but a few thousand of the remaining Jews then registered for emigration. In all, about 120,000 Jews left Iraq.

According to Gat, it is highly likely that one of Nuri as-Said's motives in trying to expel large numbers of Jews was the desire to aggravate Israel's economic problems (he had declared as such to the Arab world), although Nuri was well aware that the absorption of these immigrants was the policy on which Israel based its future. The Iraqi Minister of Defence told the U.S ambassador that he had reliable evidence that the emigrating Jews were involved in activities injurious to the state and were in contact with communist agents.

Between April 1950 and June 1951, Jewish targets in Baghdad were struck five times. Iraqi authorities then arrested 3 Jews, claiming they were Zionist activists, and sentenced two — Shalom Salah Shalom and Yosef Ibrahim Basri—to death. The third man, Yehuda Tajar, was sentenced to 10 years in prison. There has been much debate as to whether the bombs were planted by the Mossad+ to encourage Iraqi Jews to emigrate to Israel or if they were planted by Muslim extremists to help drive out the Jews. This has been the subject of lawsuits and inquiries in Israel.

The emigration law was to expire on March 1951, one year after the law was enacted. On 10 March 1951, 64,000 Iraqi Jews were still waiting to emigrate, the government enacted a new law blocking the assets of Jews who had given up their citizenship, and extending the emigration period.

Although there was a small indigenous community, most Jews in Egypt in the early twentieth century were recent immigrants to the country, who did not share the Arabic language and culture., page 233, Quote: "Not only were they not Muslim, and mainly not of Egyptian origin; most of them did not share the Arabic language and culture, either. Added to these factors was their political diversity." Many were members of the highly diverse Mutamassirun+ community, which included other groups such as Greeks, Armenians, Syrian Christians and Italians, in addition to the British and French colonial powers. Until the late 1930s, the Jews, both indigenous and new immigrants, like other minorities tended to apply for foreign citizenship in order to benefit from a foreign protection. The Egyptian government made it very difficult for non-Muslim foreigners to become naturalized. The poorer Jews, most of them indigenous and Oriental Jews, were left stateless, although they were legally eligible for Egyptian nationality. The drive to Egyptianize public life and the economy harmed the minorities, but the Jews had more strikes against them than the others. In the agitation against the Jews of the late thirties and the forties, the Jew has been seen as an enemy The Jews were attacked because of their real or alleged links to Zionism. Jews were not discriminated because of their religion or race, like in Europe, but for political reasons.

The Egyptian Prime Minister Mahmoud an-Nukrashi Pasha+ told the British ambassador:

"All Jews were potential Zionists [and] ... anyhow all Zionists were Communists."

On 24 November 1947, the head of the Egyptian delegation to the United Nations+ General Assembly, Muhammad Hussein Heykal Pasha, said, "the lives of 1,000,000 Jews in Moslem countries would be jeopardized by the establishment of a Jewish state." On 24 November 1947, Dr Heykal Pasha said: "if the U.N decide to amputate a part of Palestine in order to establish a Jewish state, ... Jewish blood will necessarily be shed elsewhere in the Arab world ... to place in certain and serious danger a million Jews. Mahmud Bey Fawzi (Egypt) said: "Imposed partition was sure to result in bloodshed in Palestine and in the rest of the Arab world."

The exodus of the foreign mutamassirun ("Egyptianized") community, which included a significant number of Jews, began following the First World War, and by the end of the 1960s the entire mutamassirun was effectively eliminated. According to Andrew Gorman, this was primarily a result of the "decolonization process and the rise of Egyptian nationalism+".

The exodus of Egyptian Jews was impacted by the 1945 Anti-Jewish Riots in Egypt+, though such emigration was not significant as the government stamped the violence out and the Egyptian Jewish community leaders were supportive of King Farouk+. In 1948, approximately 75,000 Jews lived in Egypt. Around 20,000 Jews left Egypt during 1948–49 following the events of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (including the 1948 Cairo bombings+). A further 5,000 left between 1952–56, in the wake of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952+ and later the false flag+ Lavon Affair+. The Israeli invasion as part of the Suez Crisis+ caused a significant upsurge in emigration, with 14,000 Jews leaving+ in less than six months between November 1956 and March 1957, and 19,000 further emigrating over the next decade.

In October 1956, when the Suez Crisis erupted, the position of the mutamassirun, including the Jewish community, was significantly impacted.

1,000 Jews were arrested and 500 Jewish businesses were seized by the government. A statement branding the Jews as "Zionists and enemies of the state" was read out in the mosques of Cairo and Alexandria. Jewish bank accounts were confiscated and many Jews lost their jobs. Lawyers, engineers, doctors and teachers were not allowed to work in their professions. Thousands of Jews were ordered to leave the country. They were allowed to take only one suitcase and a small sum of cash, and forced to sign declarations "donating" their property to the Egyptian government. Foreign observers reported that members of Jewish families were taken hostage, apparently to insure that those forced to leave did not speak out against the Egyptian government. Jews were expelled or left, forced out by the anti-Jewish feeling in Egypt. Some 25,000 Jews, almost half of the Jewish community left, mainly for Europe, the United States, South America and Israel, after being forced to sign declarations that they were leaving voluntarily, and agreed with the confiscation of their assets. Similar measures were enacted against British and French nationals in retaliation for the invasion. By 1957 the Jewish population of Egypt had fallen to 15,000.

In 1960, the American embassy in Cairo wrote of Egyptian Jews that: "There is definitely a strong desire among most Jews to emigrate, but this is prompted by the feeling that they have limited opportunity, or from fear for the future, rather than by any direct or present tangible mistreatment at the hands of the government."

In 1967, Jews were detained and tortured, and Jewish homes were confiscated. Following the Six Day War, the community practically ceased to exist, with the exception of several dozens of elderly Jews.

The Yemeni exodus began in 1881, seven months prior to the more well-known First Aliyah+ from Eastern Europe. The exodus came about as a result of European Jewish investment in theMutasarrifate of Jerusalem+, which created jobs for labouring Jews alongside local Muslim labour thereby providing an economic incentive for emigration. This was aided by the reestablishment of Ottoman control over the Yemen Vilayet+ allowing freedom of movement within the empire, and the opening of the Suez canal+, which reduced the cost of travelling considerably. Between 1881 and 1948, 15,430 Jews had immigrated to Palestine legally.

In 1942, prior to the formulation of the One Million Plan+, David Ben-Gurion described his intentions with respect to such potential policy to a meeting of experts and Jewish leaders, stating that "It is a mark of great failure by Zionism that we have not yet eliminated the Yemen exile [diaspora]."

If one includes Aden+, there were about 63,000 Jews in Yemen in 1948. Today, there are about 200 left. In 1947, rioters killed at least 80 Jews in Aden+, a British colony in southern Yemen. In 1948 the new Zaydi+ Imam Ahmad bin Yahya+ unexpectedly allowed his Jewish subjects to leave Yemen, and tens of thousands poured into Aden. The Israeli government's Operation Magic Carpet+ evacuated around 44,000 Jews from Yemen to Israel in 1949 and 1950.Stillman, 2003, pp. 156–57. Emigration continued until 1962, when the civil war in Yemen+ broke out. A small community remained until 1976, though it has mostly immigrated from Yemen since.

The area now known as Lebanon and Syria was the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 BCE.

In November 1945, fourteen Jews were killed in anti-Jewish riots in Tripoli+. Unlike in other Arab countries, the Lebanese Jewish community did not face grave peril during the 1948 Arab-Israel War and was reasonably protected by governmental authorities. Lebanon was also the only Arab country that saw a post-1948 increase in its Jewish population, principally due to the influx of Jews coming from Syria and Iraq.Parfitt, Tudor. (2000) p. 91.

In 1948, there were approximately 24,000 Jews in Lebanon. The largest communities of Jews in Lebanon were in Beirut+, and the villages near Mount Lebanon+, Deir al Qamar+, Barouk+,Bechamoun+, and Hasbaya+. While the French mandate saw a general improvement in conditions for Jews, the Vichy regime placed restrictions on them. The Jewish community actively supported Lebanese independence+ after World War II and had mixed attitudes toward Zionism.

However, negative attitudes toward Jews increased after 1948, and, by 1967, most Lebanese Jews had emigrated—to Israel, the United States, Canada, and France. In 1971, Albert Elia, the 69-year-old Secretary-General of the Lebanese Jewish community, was kidnapped in Beirut by Syrian agents and imprisoned under torture in Damascus+, along with Syrian Jews who had attempted to flee the country. A personal appeal by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees+, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan+, to the late President Hafez al-Assad+ failed to secure Elia's release.

The remaining Jewish community was particularly hard hit by the civil war in Lebanon+, and by the mid-1970s, the community collapsed. In the 1980s, Hezbollah+ kidnapped several Lebanese Jewish businessmen, and in the 2004 elections, only one Jew voted in the municipal elections. There are now only between 20 and 40 Jews living in Lebanon.[http://www.jewcy.com/religion-and-beliefs/jews_lebanon_another_perspective The Jews of Lebanon: Another Perspective

In 1947, rioters in Aleppo+ burned the city's Jewish quarter+ and killed 75 people.Daniel Pipes, ''Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 57, records 75 victims of the Aleppo massacre. As a result, nearly half of the Jewish population of Aleppo opted to leave the city,Shindler, Colin. ''A history of modern Israel.'' Cambridge University Press 2008. pp. 63–64. initially to neighbouring Lebanon.

In 1948, there were approximately 30,000 Jews in Syria. In 1949, following defeat in the Arab-Israeli War, the CIA-backed March 1949 Syrian coup d'état+ installed Husni al-Za'im+ as the President of Syria. Za'im permitted the emigration of large numbers of Syrian Jews, and 5,000 left to Israel.

The subsequent Syrian governments placed severe restrictions on the Jewish community, including barring emigration. Over the next few years, many Jews managed to escape, and the work of supporters, particularly Judy Feld Carr+,Levin, 2001, pp. 200–201. in smuggling Jews out of Syria, and bringing their plight to the attention of the world, raised awareness of their situation. Although the Syrian government attempted to stop Syrian Jews from exporting their assets, the American consulate in Damascus noted in 1950 that "the majority of Syrian Jews have managed to dispose of their property and to emigrate to Lebanon, Italy, and Israel"

In November 1954, the Syrian government lifted the ban on Jewish emigration.

While most Jews had left by the wake of the 1973 October War+, there was still a sizable community residing in Syria, which however also continued to decrease over the years. A 2,000 strong Syrian Jewish community remained in Syria during Hafez al-Assad rule, but almost entirely left the country in the early 1990s, leaving for the United States.

Following the Madrid Conference of 1991+ the United States put pressure on the Syrian government to ease its restrictions on Jews, and on Passover in 1992, the government of Syria began granting exit visas to Jews on condition that they do not emigrate to Israel. At that time, the country had several thousand Jews. The majority of the Jewish community left for the United States, although some went to France and Turkey, and those who wanted to go to Israel were brought there in a two-year covert operation. There is a large and vibrant Syrian Jewish community in South Brooklyn+, New York. In 2004, the Syrian government attempted to establish better relations with the emigrants, and a delegation of a dozen Jews of Syrian origin visited Syria in the spring of that year.

As of December 2014 with all of the violence and unstable government in Syria only 17 Jews remain according to Rabbi Avraham Hamra with nine men and eight women all over sixty years of age.

Bahrain+'s tiny Jewish community, mostly the Jewish descendants of immigrants who entered the country in the early 20th century from Iraq, numbered 600 in 1948. In the wake of the 29 November 1947 U.N. Partition vote, demonstrations against the vote in the Arab world were called for 2–5 December. The first two days of demonstrations in Bahrain saw rock throwing against Jews, but on 5 December+, mobs in the capital of Manama+ looted Jewish homes and shops, destroyed the synagogue, beat any Jews they could find, and murdered one elderly woman.

Over the next few decades, most left for other countries, especially Britain; as of 2006 only 36 remained.Larry Luxner, , ''Jewish Telegraphic Agency+'', 18 October 2006. Accessed 25 October 2006.

During the years of 1892 to 1910, there had been a few pogroms against Jews, in Shiraz+ and other towns, culminating in 1910 Shiraz blood libel+, resulting in thirteen deaths, injury, robbery, vandalism and near-starvation for the 6,000 Jews of Shiraz.

Historian Ervand Abrahamian+ estimates 50,000 Jews were living in Iran around 1900, with majority of them residing in Yazd+, Shiraz, Tehran+, Isfahan+ and Hamadan+.

The violence and disruption in Arab life associated with the founding of Israel in 1948 drove an increased anti-Jewish sentiment in neighbouring Iran as well. According to Trita Parsi+, by 1951 only 8,000 of 100,000 Iranian Jews chose to emigrate to Israel.Parsi, T. ''Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States''. Yale University Press. pp. 64–65.

Anti-Jewish sentiment was on the rise under prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh+, and continued until 1953, in part because of the weakening of the central government and strengthening of clergy in the political struggles between the shah and Mossadegh. According to Eliz Sanasarian+, from 1948–1953 about one-third of Iranian Jews, most of them poor, emigrated to Israel.Sanasarian (2000), p. 47 After the deposition of Mossadegh in 1953, the reign of shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi+ was the most prosperous era for the Jews of Iran. According to the first national census taken in 1956, Jewish population in Iran stood at 65,232, but there is no reliable data about migrations in the first half of the 20th century. David Littman+ puts the total figure of emigrants to Israel in 1948–1978 at 70,000.Littman (1979), p. 5.

The tensions between the loyalists of the Shah and Islamists through the 1970s initiated the mass-migration of Iranian Jews, first affecting the higher-class. Instability caused thousands of Persian Jews to leave Iran prior to revolution+ - some seeking better economic opportunities or stability, while others afraid of the potential Islamic takeover.

Prior to the Islamic revolution in 1979, some 80,000 Jews lived in Iran, primarily in the capital Teheran. Since the revolution, the Persian Jewish community has experienced a collapse, plunging to about one fourth of its size within three decades, and continues to shrink to this day. The current Jewish population of Iran is 8,756 according to the most recent Iranian census. As a result of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, 60,000 of the 80,000 Jews in Iran fled, of whom 35,000 went to the United States, 25,000 went to Israel, and 5,000 went to Europe (mainly to the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland About 15% of the Persian Jewish community in Israel were admitted between 1975 and 1991.

At the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, 60,000 Jews were still living in Iran. From then on, Jewish emigration from Iran dramatically increased, as about 30,000 Jews left within several months of the revolution alone.Littman (1979), p. 5. Since the Revolution, Iran's Jewish population, some 30,000 Jews, have emigrated to the United States, Israel, and Europe. In 1979, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini+ met with the Jewish community upon his return from exile in Paris and issued a ''fatwa+'' decreeing that the Jews were to be protected.

Some sources put the Iranian Jewish population in the mid and late 1980s as between 50,000–60,000. An estimate based on the 1986 census put the figure considerably higher for the same time, around 55,000. In the 1990s there has been more uniformity in the figures, with most sources since then estimating roughly 25,000 Jews remaining in Iran. The migration of Persian Jews after Iranian Revolution is mostly attributed to fear of religious persecution,Mahdī, A. A. and Daniel, E. L. ''Culture and Customs of Iran''. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2006: P60. ISBN 0-313-32053-5 economic hardships and insecurity after the deposition of the Shah regime and consequent domestic violence+ and the Iran–Iraq War+. While Iranian constitution generally respects minority rights of non-Muslims (though there are some forms of discrimination), the strong anti-Zionist policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran created a tense and uncomfortable situation for Iranian Jews, who became vulnerable for accusation on alleged collaboration with Israel.

The United States State Department estimated the number of Jews in Iran at 20,000–25,000 as of 2009. The 2012 census did put the figure of remaining Jewish community in Iran at about 9,000.

When the Republic of Turkey was established in 1923, Aliyah+ was not particularly popular among Turkish Jewry; migration from Turkey to Palestine was minimal in the 1920s.

During 1923-1948, approximately 7,300 Jews emigrated from Turkey to Palestine+. After the 1934 Thrace pogroms+ following the 1934 Turkish Resettlement Law+, immigration to Palestine increased; it is estimated that 521 Jews left for Palestine from Turkey in 1934 and 1,445 left in 1935. Immigration to Palestine was organized by the Jewish Agency and the Palestine Aliya Anoar Organization. The Varlık Vergisi+, a capital tax established in 1942, was also significant in encouraging emigration from Turkey to Palestine; between 1943 and 1944, 4,000 Jews emigrated."

The Jews of Turkey reacted very favorably to the creation of the State of Israel. Between 1948 and 1951, 34,547 Jews immigrated to Israel, nearly 40% of the Jewish population at the time. Immigration was stunted for several months in November 1948, when Turkey suspended migration permits as a result of pressure from Arab countries.

In March 1949, the suspension was removed when Turkey officially recognized Israel, and emigration continued, with 26,000 emigrating within the same year. The migration was entirely voluntary, and was primary driven by economic factors given the majority of emigrants were from the lower classes. In fact, the migration of Jews to Israel is the second largest mass emigration wave out of Turkey, the first being the population exchange between Greece and Turkey+.

After 1951, emigration of Jews from Turkey to Israel slowed materially.

In the mid 1950s, 10% of those who had moved to Israel returned to Turkey. A new synagogue, the Neve Şalom+, was constructed in Istanbul+ in 1951. Generally, Turkish Jews in Israel have integrated well into society and are not distinguishable from other Israelis. However, they maintain their Turkish culture and connection to Turkey, and are strong supporters of close relations between Israel and Turkey+.

Even though historically speaking populist antisemitism was rarer in the Ottoman Empire and Anatolia+ than in Europe, since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, there has been a rise in antisemitism. On the night of 6–7 September 1955, the Istanbul pogrom+ was unleashed. Although primarily aimed at the city's Greek population+, the Jewish and Armenian+ communities of Istanbul were also targeted to a degree. The caused damage was mainly material - more than 4,000 shops and 1,000 houses belonging to Greeks, Armenians and Jews were destroyed - but it deeply shocked minorities throughout the country

Since 1986, increased attacks on Jewish targets throughout Turkey impacted the security of the community, and urged many to emigrate. The Neve Shalom Synagogue in Istanbul has been attacked by Islamic militants+ three times. On 6 September 1986, Arab terrorists gunned down 22 Jewish worshippers and wounded 6 during ''Shabbat+'' services at Neve Shalom. This attack was blamed on the Palestinian+ militant Abu Nidal+. In 1992, the Lebanon-based Shi'ite Muslim+ group of Hezbollah carried out a bombing against the Synagogue, but nobody was injured. The Synagogue was hit again during the 2003 Istanbul bombings+ alongside theBet Israel Synagogue+, killing 20 and injuring over 300 people, both Jews and Muslims alike.

Despite the increasing anti-Israeli and anti-Jewish attitudes in modern Turkey, the country's Jewish community there is still believed to be the largest among Muslim countries, numbering about 26,000.

The Afghan Jewish community declined from about 40,000 in the early 20th Century to 5,000 by 1934.

In 1933, following the assassination of Mohammed Nadir Shah+, King of Afghanistan, a number of Jews in Afghanistan were expelled from certain towns in which they dwelled and robbed of their property.. Jews continued living in major cities such as Kabul and Herat, under restrictions on work and trade.

The obscurity of the country and the fact that Jews were facing persecution around the world at the time, meant that their experiences were generally ignored. Germany was influential in Afghanistan and regarded the Afghans (like the Iranians) as Aryans.

Jews were allowed to emigrate in 1951 and most moved to Israel and the United States.New York, 19 June 2007 (RFE/RL+), By 1969, some 300 remained, and most of these left after the Soviet invasion of 1979+, leaving 10 Afghan Jews in 1996, most of them in Kabul+. More than 10,000 Jews of Afghan descent presently live in Israel. Over 200 families of Afghan Jews live in New York City.

At the time of Pakistani independence in 1947+, some 1,300 Jews remained in Karachi+, many of them Bene Israel+ Jews, observing Sephardic+ Jewish rites. Other communities of Baghdadi Jews+ and Mizrahi Jews+ from Iran were found in the city. A small Ashkenazi+ population was also present in the city. Some Karachi streets still bear names that hark back to a time when the Jewish community was more prominent; such as Ashkenazi Street, Abraham Reuben Street (named after the former member of the Karachi Municipal Corporation), Ibn Gabirol Street, and Moses Ibn Ezra Street—although some streets have been renamed, they are still locally referred to by their original names. A small Jewish graveyard still exists in the vast Mewa Shah Graveyard+ near the shrine of a Sufi saint. The neighbourhood of Baghdadi in Lyari Town+ is named for the Baghdadi Jews who once lived there. A community of Bukharan Jews+ was also found in the city of Peshawar+, where many buildings in the old city feature a Star of David+ as exterior decor as a sign of the Hebrew origins of its owners. Members of the community settled in the city as merchants as early as the 17th century, although the bulk arrived as refugees fleeing the advance of the Russian Empire into Bukhara+, and later the Russian Revolution in 1917. Both the Jewish communities in Karachi and Peshawar have since been almost entirely decimated.

The exodus of Jews from Pakistan to Bombay+ and other cities in India came just prior to the creation of Israel in 1948, when anti-Israeli sentiments rose. By 1953, fewer than 500 Jews were reported to reside in all of Pakistan. Anti-Israeli sentiment and violence often flared during ensuing conflicts in the Middle East, resulting in a further movement of Jews out of Pakistan. Presently, a large number of Jews from Karachi live in the city of Ramla+ in Israel.

The Jewish community in Sudan was concentrated in the capital Khartoum+, and had been established in the late 19th century. By the middle of the 20th century the community included some 350 Jews, mainly of Sephardic background, who had constructed a synagogue and a Jewish school. Between 1948 and 1956, some members of the community left the country, and it finally ceased to exist by the early 1960s.M. Cohen, ''Know your people, Survey of the world Jewish population''. 1962.I. Nakham, ''The notebook of the Jewish community of Sudan''.

The Jewish population in East Bengal+ was 200 at the time of the Partition of British India+ in 1947. They included a Baghdadi Jew+ish merchant community that settled in Dhaka+ during the 17th-century. A prominent Jew in East Pakistan+ was Mordecai Cohen, who was a Bengali and English newsreader on East Pakistan Television. By the late 1960s, much of the Jewish community had left for Calcutta+.

In 1948, there were between 758,000 and 881,000 Jews (see table below) living in communities throughout the Arab world. Today, there are fewer than 8,600. In some Arab states, such as Libya, which was about 3% Jewish, the Jewish community no longer exists; in other Arab countries, only a few hundred Jews remain.

|+ '''Jewish Population by country: 1948, 1972, 2000 and recent times'''

! Country or territory

! 1948 Jewish

population

! 1972 Jewish

population

! Modern estimates

| Morocco

250,000–265,000

31,000

2,500–2,700 (2006)Sergio DellaPergola, , 2012, p. 62

| Algeria

140,000Stearns, 2001, p. 966.

1,000

≈0

| Tunisia

50,000–105,000

8,000

900–1,000 (2008)

| Libya

35,000–38,000

50

0

| '''Maghreb Total'''

'''475,000–548,000'''

'''40,050'''

'''3,400–3,700'''

| Iraq

135,000–140,000

500

5

| Egypt

75,000–80,000

500

100 (2006)

| Yemen and Aden

formatnum: #expr: (45000+8000): –formatnum: #expr: (55000+8000):

500

330–350.

| Syria

15,000–30,000

4,000

100 (2006)

| Lebanon

5,000–20,000

2,000

20–40

| Bahrain

550–600

50

| Sudan

350

≈0

| '''Arab Countries Total'''

'''758,350–881,350'''

'''<4,500'''

| Afghanistan

5,000

500

1

| Bangladesh

Unknown

|

175–3,500

| Iran

65,232 (1956)

62,258 (1976) - 80,000

9,252 (2006) - 10,800 (2006)

| Pakistan

2,000–2,500

250

200

| Turkey

80,000

30,000Leon Shapiro, "World Jewish Population, 1972 Estimates". ''American Jewish Year Book'' vol. 73 (1973), pp. 522–529.

17,800 (2006)

| '''Non-Arab Muslim Countries Total'''

'''202,000–282,500'''

'''110,750'''

'''32,100'''

|

Of the nearly 900,000 Jewish emigrants, approximately 680,000 emigrated to Israel and 235,000 to France; the remainder went to other countries in Europe as well as to the Americas. About two thirds of the exodus was from the Maghreb region, of which Morocco's Jews went mostly to Israel, Algeria's Jews went mostly to France, and Tunisia's Jews departed for both countries.

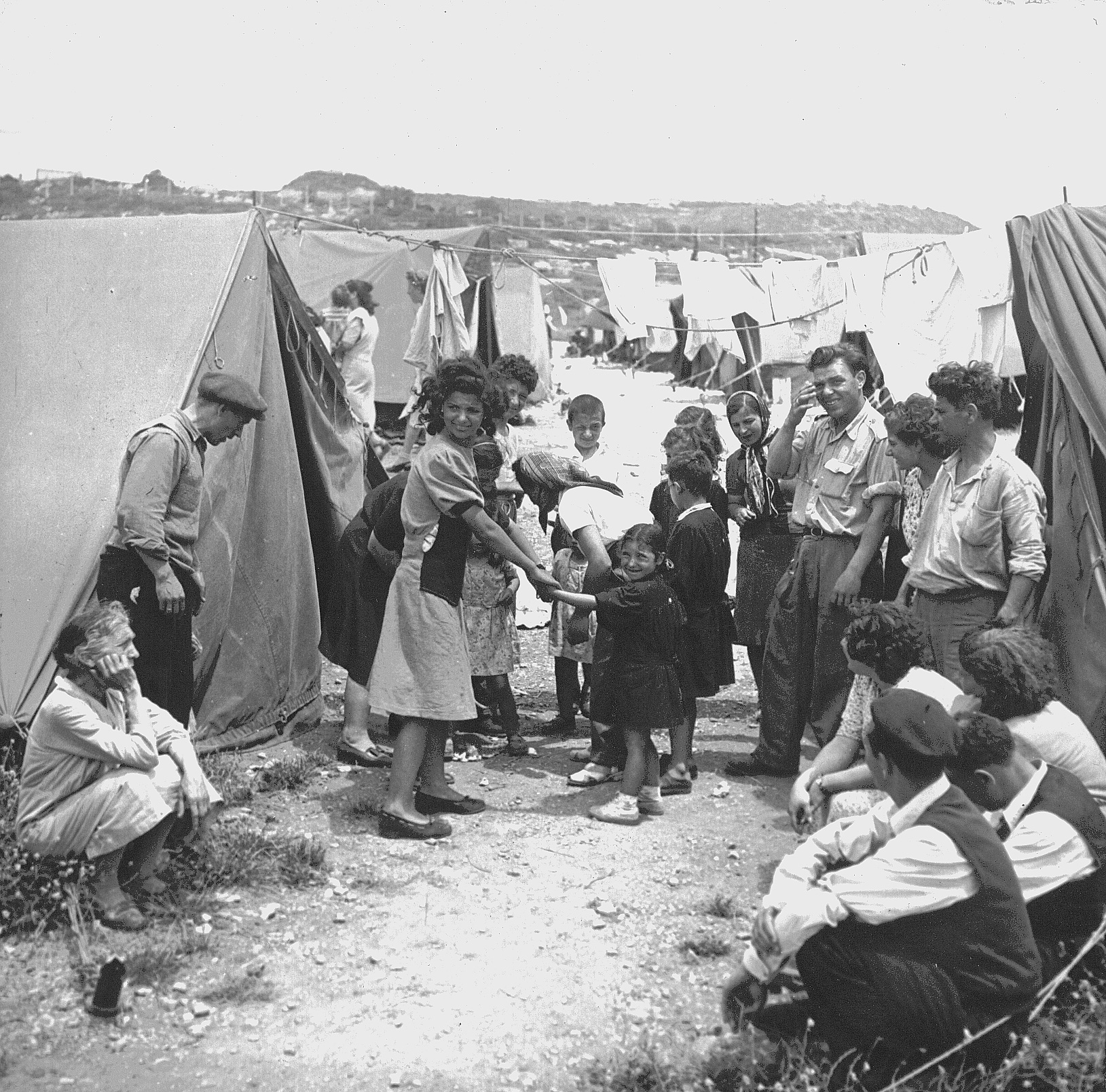

The majority of Jews in Arab countries eventually immigrated to the modern State of Israel.Stillman, 2003, p. xxi. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were temporarily settled in the numerousimmigrant camps+ throughout the country. Those were later transformed into ma'abarot+ (transit camps), where tin dwellings were provided to house up to 220,000 residents. The ma'abarot existed until 1963. The population of transition camps was gradually absorbed and integrated into Israeli society. Many of the North African and Middle-Eastern Jews had a hard time adjusting to the new dominant culture, change of lifestyle and there were claims of discrimination. By 2003 they and their offspring, (including those of mixed lineage) comprised 3,136,436 people, or about 61% of Israel's Jewish population+.

France was also a major destination and about 50% (300,000 people) of modern French Jews have roots from North Africa. In total, it is estimated that between 1956 and 1967, about 235,000 North African Jews from Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco immigrated to France due to the decline of the French Empire and following the Six-Day War.

The United States was a destination of many Egyptian, Lebanese and Syrian Jews.

Advocacy groups acting on behalf of Jews from Arab countries include:

* World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries+ (WOJAC) seeks to secure rights and redress for Jews from Arab countries who suffered as a result of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

* Justice for Jews from Arab Countries+

* JIMENA+ (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa) publicizes the history and plight of the 850,000 Jews indigenous to the Middle East+ and North Africa+ who were forced to leave their homes and abandon their property, who were stripped of their citizenship

* HARIF+ (UK Association of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa) promotes the history and heritage of Jews from the Arab and Muslim world

* Historical Society of the Jews from Egypt+ and International Association of Jews from Egypt+

* Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center+

WOJAC, JJAC and JIMENA have been active in recent years in presenting their views to various governmental bodies in the US, Canada and UK, among others, as well as appearing before theUnited Nations Human Rights Council+.

In 2003, was introduced into the House of Representatives+ by pro-Israel congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen+. In 2004 simple resolution+s and were issued into the House of Representatives and Senate+ by Jerrold Nadler+ and Rick Santorum+, respectively. In 2007 simple resolutions and were issued into the House of Representatives and Senate. The resolutions had been written together with lobbyist group JJAC+, whose founder Stanley Urman described the resolution in 2009 as "perhaps our most significant accomplishment" The House of Representatives resolution was sponsored by Jerrold Nadler, who followed the resolutions in 2012 with House Bill . The 2007-08 resolutions proposed that any "comprehensive Middle East peace agreement to be credible and enduring, the agreement must address and resolve all outstanding issues relating to the legitimate rights of all refugees, including Jews, Christians and other populations displaced from countries in the Middle East", and encourages President Barack Obama+ and his administration to mention Jewish and other refugees when mentioning Palestinian refugees at international forums. The 2012 bill, which was moved to committee, proposed to recognize the plight of "850,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries", as well as other refugees, such as Christians from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf.

Jerrold Nadler explained his view in 2012 that "the suffering and terrible injustices visited upon Jewish refugees in the Middle East needs to be acknowledged. It is simply wrong to recognize the rights of Palestinian refugees without recognizing the rights of nearly 1 million Jewish refugees who suffered terrible outrages at the hands of their former compatriots."

The issue of comparison of the Jewish exodus with the Palestinian exodus was raised by the Israeli Foreign Ministry as early as 1961.

In 2012, a special campaign on behalf of the Jewish refugees from Arab countries was established and gained momentum. The campaign urges the creation of an international fund that would compensate both Jewish and Palestinian Arab+ refugees, and would document and research the plight of Jewish refugees from Arab countries. In addition, the campaign plans to create a national day of recognition in Israel to remember the 850,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries, as well as to build a museum that would document their history, cultural heritage, and collect their testimony.

On 21 September 2012, a special event was held at the United Nations to highlight the issue of Jewish refugees from Arab countries. Israeli ambassador Ron Prosor+ asked the United Nations to "establish a center of documentation and research" that would document the "850,000 untold stories" and "collect the evidence to preserve their history", which he said was ignored for too long. Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon+ said that "We are 64 years late, but we are not too late." Diplomats from approximately two dozen countries and organizations, including the United States, the European Union, Germany, Canada, Spain, and Hungary attended the event. In addition, Jews from Arab countries attended and spoke at the event.

In response to the Palestinian Nakba narrative, the term "Jewish Nakba" is sometimes used to refer to the persecution and expulsion of Jews from Arab countries in the years and decades following the creation of the State of Israel. Israeli columnist Ben Dror Yemini+, himself a Mizrahi Jew, wrote:

::However, there is another Nakba: the Jewish Nakba. During those same years [the 1940s], there was a long line of slaughters, of pogroms, of property confiscation and of deportations against Jews in Islamic countries. This chapter of history has been left in the shadows. The Jewish Nakba was worse than the Palestinian Nakba. The only difference is that the Jews did not turn that Nakba into their founding ethos. To the contrary.

Professor Ada Aharoni+, chairman of The World Congress of the Jews from Egypt, argues in an article entitled "What about the Jewish Nakba?" that exposing the truth about the expulsion of the Jews from Arab states could facilitate a genuine peace process, since it would enable Palestinians to realize they were not the only ones who suffered, and thus their sense of "victimization and rejectionism" will decline.

Additionally, Canadian MP and international human rights lawyer Irwin Cotler+ has referred to the "double Nakba". He criticizes the Arab states' rejectionism of the Jewish state, their subsequent invasion to destroy the newly formed nation, and the punishment meted out against their local Jewish populations:

::The result was, therefore, a double Nakba: not only of Palestinian-Arab suffering and the creation of a Palestinian refugee problem, but also, with the assault on Israel and on Jews in Arab countries, the creation of a second, much less known, group of refugees—Jewish refugees from Arab countries.

Iraqi-born Ran Cohen+, a former member of the Knesset+, said: "I have this to say: I am not a refugee. I came at the behest of Zionism, due to the pull that this land exerts, and due to the idea of redemption. Nobody is going to define me as a refugee." Yemeni-born Yisrael Yeshayahu+, former Knesset speaker, Labor Party, stated: "We are not refugees. [Some of us] came to this country before the state was born. We had messianic aspirations." And Iraqi-born Shlomo Hillel+, also a former speaker of the Knesset, Labor Party, claimed: "I do not regard the departure of Jews from Arab lands as that of refugees. They came here because they wanted to, as Zionists."

Historian Tom Segev+ stated: "Deciding to emigrate to Israel was often a very personal decision. It was based on the particular circumstances of the individual's life. They were not all poor, or 'dwellers in dark caves and smoking pits'. Nor were they always subject to persecution, repression or discrimination in their native lands. They emigrated for a variety of reasons, depending on the country, the time, the community, and the person."

Iraqi-born Israeli historian Avi Shlaim+, speaking of the wave of Iraqi Jewish migration to Israel, concludes that, even though Iraqi Jews were "victims of the Israeli-Arab conflict", Iraqi Jews aren't refugees, saying "nobody expelled us from Iraq, nobody told us that we were unwanted." He restated that case in a review ofMartin Gilbert+'s book, ''In Ishmael's House''.

Yehuda Shenhav+ has criticized the analogy between Jewish emigration from Arab countries and the Palestinian exodus. He also says "The unfounded, immoral analogy between Palestinian refugees and Mizrahi immigrants needlessly embroils members of these two groups in a dispute, degrades the dignity of many Mizrahi Jews, and harms prospects for genuine Jewish-Arab reconciliation." He has stated that "the campaign's proponents hope their efforts will prevent conferral of what is called a 'right of return' on Palestinians, and reduce the size of the compensation Israel is liable to be asked to pay in exchange for Palestinian property appropriated by the state guardian of 'lost' assets."

Israeli historian Yehoshua Porath+ has rejected the comparison, arguing that while there is a superficial similarity, the ideological and historical significance of the two population movements are entirely different. Porath points out that the immigration of Jews from Arab countries to Israel, expelled or not, was the "fulfilment of a national dream". He also argues that the achievement of this Zionist goal was only made possible through the endeavors of the Jewish Agency's agents, teachers, and instructors working in various Arab countries since the 1930s. Porath contrasts this with the Palestinian Arabs' flight of 1948 as completely different. He describes the outcome of the Palestinian's flight as an "unwanted national calamity" that was accompanied by "unending personal tragedies". The result was "the collapse of the Palestinian community, the fragmentation of a people, and the loss of a country that had in the past been mostly Arabic-speaking and Islamic. "

Alon Liel, a former director-general of the Foreign Ministry says that many Jews escaped from Arab countries, but he does not call them "Refugees" since his definition for the term "Refugee" is different from UNWRA+'s definition+.

Palestinian politician Hanan Ashrawi+ has argued that Jews from Arab lands are not refugees at all and that Israel is using their claims in order to counterbalance to those of Palestinian refugees against it. Ashrawi said that "If Israel is their homeland, then they are not 'refugees'; they are emigrants who returned either voluntarily or due to a political decision."

In Libya, Iraq and Egypt many Jews lost vast portions of their wealth and property as part of the exodus because of severe restrictions on moving their wealth out of the country.

In the Maghreb, the situation was more complex. For example, in Morocco emigrants were not allowed to take more than $60 worth of Moroccan currency with them, although generally they were able to sell their property prior to leaving,

Yemeni Jews were usually able to sell what property they possessed prior to departure, although not always at market rates.